Personal Protection

Concepts for survival in the street

by Andrew Williams, Rolf Clausnitzer and David Peterson

*** Published Australasian Martial Arts' magazine (NZ) Vol 6/issue 6, 1999/2000 and Vol 7/issue 1, Feb/March 2000 ***

Personal Protection is a relatively new phenomenon in the field of self defence. In fact, it represents a radical departure from the somewhat limited vision presented by most traditional self-defence systems.

It is inspired by and based on two major influences:

1. The work done by two very respected and experienced (in terms of both tournament performance and real life confrontations) British martial artists, Geoff Thompson and Peter Consterdine; and

2. The highly efficient and practical Chinese martial art of Wing Chun Kuen which, interestingly, Messrs. Thompson and Consterdine acknowledge in their video series, “The Pavement Arena”, as having had a major influence on their own self protection philosophy and methods.

Wing Chun is a major Chinese martial art or system that is unparalleled in its suitability for today’s urban environment. It is radically different in its general approach from that of most traditional martial arts, as it is not reliant on strength, balletic poise, acrobatic movements, or a complexity of often flamboyant techniques. Instead of being technique oriented and requiring students to learn by rote an endless variety of movements (which often result in a mental “log jam” in real life situations), Wing Chun is based on a clear understanding of fighting concepts and strategies, expressed via a minimal number of techniques which meet the basic criteria of simplicity, directness and efficiency.

Although widely believed to have been founded and developed by a Buddhist nun, Ng Mui, and her female pupil, Yim Wing Chun, about 200 hundred years ago, Wing Chun has evolved over time via a process of “natural selection”, with a continual discarding of superfluous, complex and ineffective techniques and movements. It is the system that the legendary Bruce Lee used as the foundation of his own combat philosophy of Jeet Kune Do, and has become the most influential style of Kung Fu, allowing even traditional Karate and other Kung Fu practitioners to reappraise and enhance their own skills and techniques.

Successfully tested in real “no-holds barred” fights against numerous other styles in Hong Kong in the 1950′s and early 1960′s by outstanding students of Grandmaster Yip Man, such as the late Sifu Wong Shun Leung and Sifu Wang Kiu, Wing Chun is considered to be one of the most, if not the most practical and efficient martial arts for use in today’s increasingly violent environment. In simple terms, Wing Chun is the “Science of Street Fighting“, designed solely for the purpose of surviving an attack by being a better attacker than one’s assailant. Hence it forms the perfect basis for the concept of Personal Protection.

It should be made clear at the outset that this document is only a basic guideline, not intended to be, or taken for, a comprehensive and definitive work. For example, it does not purport to supply the reader with an in depth examination of an attacker’s psychology. Nor is it a typical “how to” manual, detailing specific, complicated self-defence techniques in make believe, often unrealistic situations. It is certainly not intended to lead the reader through a sequence of events culminating in the inevitable limiting solution.

It is the sincere wish of the authors, however, to encourage readers to take a closer and more realistic look at the concept of personal security, a good understanding of which, under the guidance of an experienced and competent instructor, can provide a sound basis for developing a practical and effective method of self protection. It should be stressed, of course, in view of the complexity of the subject, that this article is not to be taken as a “quick fix”, ready-made set of rules for instant implementation. Considerable analysis, discussion, and testing are called for, as any one of the main ideas or principles outlined could itself become the theme for an entire seminar. Further, a particular idea may not automatically fit in with your philosophy of fighting or it may need to be modified accordingly.

It should be pointed out at this stage that, as few of us can rely on great physical strength, it is vital that the instructor has a clear understanding of power generation utilising an informed understanding of exercise methodologies and biomechanics, thus enabling the students to realise their full striking potential. An open mind is called for, far removed from the “arm lock” mentality* of many martial arts systems, not only to get the most out of the concepts presented in this paper, but also to get the best out of those inherent in all martial arts.

Personal Protection is not a sport, but a serious approach to preparing oneself for potential real life threats. To quote an ancient Chinese sage, Li Chuan, “War is a grave matter. One is apprehensive lest men embark on it without due reflection”. A skilful fighter is one who is able to triumph over his or her opponent by having a deep understanding of their own capabilities and potential. Therefore, the proper training is essential, training that prepares you not only physically, but mentally and emotionally as well.

As stated at the beginning of this article, Personal Protection is certainly a departure from the countless “self defence” instruction methods, widely depicted, showing attackers in unrealistic, static, even clumsily inept poses, telegraphing their movements, and “allowing” themselves to be handled with impunity by the defender. And it is certainly not an exploration of the dramatic scenario so popular with idealistic and inexperienced instructors in countless martial arts clubs around

the world, where the two antagonists conduct a gentlemanly bout to decide who is the better man, two noble warriors observing a set of rules and a pattern of ritualistic behaviours, who by mutual consent begin a dignified exchange of technique.

*ie: the mentality that many martial artists exhibit, in that they will try to make a technique fit the situation (eg: try to put their opponent in an arm-lock), no matter what, becoming, in the words of Master Sifu Wong Shun Leung, “…a slave to their art, instead of a master of it”

In the street, the classical depiction of a defender representing a particular martial art squaring off against an attacker from another system is seldom, if ever, encountered. Violence can erupt with little or no sign of threat. And this eruption is usually in the form of a vicious, spiteful act, carried out with deadly intent, with no regard for the rules of civilised conduct and little, if any, resemblance to the set piece duel in the dojo or kwoon. In the street, almost every conceivable weapon, from keys and cutting weapons to baseball bats and house bricks, is used to inflict pain, serious injury, and even death. And it is here that you are more likely to be savagely bitten by a crazed attacker than to be stopped by a beautifully executed roundhouse kick to the head.

It should also be noted that few of us these days have the “luxury” of testing our fighting skills in real combat situations. As such, we are usually unable to duplicate the enormous amounts of emotional pressure that accompany a real fight in the practise of sparring or ‘Chi Sau’. Both lack the physical and verbal aggression so often used by remorseless street opponents.

Most acts of violence and physical abuse are carried out in familiar surroundings, by people one knows. They can be long term, and often occur in the home, perpetrated by a family member or so called friend, and if you are unable or unwilling to confront these cowardly individuals, your best long term defence is to use the laws that are in place to protect you.

Not all attacks, however, occur in the home and not all the perpetrators are known. They are usually carried out by vicious, cowardly individuals and/or people seeking monetary gain. It has been said that 99% of these attacks are opportunistic, ie. they are not pre planned but occur at the time because the “conditions” seem right to the attacker(s).

Environmentally, there are two “basic” ways in which you may be attacked. Firstly, your attacker can strike suddenly from a concealed position, utilising the element of surprise. The object is to catch you unawares and subject you to enormous pressure, mentally, physically and, most importantly, emotionally. The sudden change in your emotional state is effected by the body’s reaction to threat, which is normally experienced as fear. If this reaction is uncontrolled, you will limit or waste your chance to react or retaliate in an effective manner, whether that is to run or to stand and fight. The attacker can use a multitude of situations in which to stage an ambush. This would of course dictate that one needs a highly developed sense of subliminal threat awareness in order to minimise the possibility of being attacked and/or surprised. As it is improbable, however, that one could remain vigilant all of the time, the next best option is to train in such a way as to develop a high degree of control over your body’s reaction to threat. This type of instruction requires a high degree of realism and honesty within your training regime, never accepting a protective technique just because it looks like it would or could work. It requires the continual testing of the limits of your emotional capabilities in a threatening and violent environment.

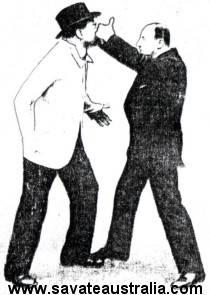

Another method of attack would be for the opponent to confront you at a very close range, employing psychological tactics. Your attacker needs to be close so that you feel the full force of their aggressive tactic. These tactics can vary greatly, but their underlying purpose is to engage your thought processes and hence control your corresponding emotional reactions in some way, to make you more vulnerable to attack. As in the ambush scenario, fear is a major weapon in the arsenal of the attacker, who may adopt aggressive tactics, where prodding, shoving, abusive and threatening language, and menacing, threatening gestures may all be utilised to create fear and even panic. On the other hand, the attacker may decide to adopt the very different strategy of appearing to be non-threatening, by behaving in a disarming and deceptive manner. He may ask you a seemingly harmless question designed not to upset you, but to distract you in some way, thereby making you vulnerable to a sudden attack because you are in a more relaxed state and off your guard. Here the attacker relies on the ability to launch his attack without you being aware of their intention, and again it is worth considering the distance this is best achieved from.

Distance Management

Amidst the endless variations and combinations of ambushes, surprise attacks, and openly aggressive assaults, it is very important to bear in mind that it is nearly always the attacker who dictates (or intends to dictate) the physical distance at which the confrontation and assault will take place. It is somewhat ludicrous to believe that this distance is the one usually depicted in martial arts movies, or the regimented distance at which sporting competitors begin their exchanges in tournaments. In reality, it is the distance where the victim can be struck with little warning and the full impact of an aggressive approach can be felt. It is the distance where one may engage another in polite conversation, or to stop to ask for directions or the time. The distance is almost, without exception, punching, kneeing, headbutting or stabbing distance. It is only logical, from the attacker’s viewpoint to utilise this range. Afterall, why would you allow someone to have the room to manoeuvre or recognise your initial movement to strike them?

If you accept this notion, and from our personal experience, and from the related experiences of our peers, we believe it to be true, and if you are serious in your intentions to teach or learn practical self-protection, then this is the distance you will base most, if not all of your training strategies, tactics, and power development drills for Personal Protection. It would require enormous discipline to remain fully aware all the time, and the nature of most societies would make it almost impossible to maintain a personal safety area that would inhibit an attacker’s intention to get within striking distance, so the ability to recognise ritualised patterns of assault behaviour is essential.

The Victim Syndrome

On their videotape entitled “The Pavement Arena”, Geoff Thompson and Peter Consterdine say that a booby trap or bomb is deemed to be victim operated. So it is that in many instances an attack on yourself can be said to be victim operated. You can make yourself a victim by your lack of awareness, your meek demeanour and other body language. Once you understand, and more importantly, practise the concepts and strategies of Personal Protection, however, you will be able to project a more positive and confident image. It will enable you to become more aware of someone’s intention to attack you. Put yourself in the attacker’s position, …whom would you attack? Someone who presents a formidable target, or a person who looks like a pushover?

December 1993

I had to return to my car in the dark. The area was renowned for being dangerous at night and I was nervous to be alone. I walked on the footpath close to the road and watched each door and alleyway for movement. I walked into the car park and kept close to the middle of the driveway lest someone was waiting in ambush. I would look over my shoulder as a matter of routine whilst maintaining a steady, even pace. I was about twenty metres from my car when I could make out two people near where I remembered parking my vehicle. As I drew closer, I could see that they were at the rear of my car. One man was crouched and was busying himself with my bike rack which was attached to the car’s tow-bar. The other guy leaned casually on the boot of my car, smoking a cigarette. I was about five metres away when the smoking man became aware of me, and he looked in my direction and said, “G’day mate.”

I was shocked. He seemed so casual and displayed no concern that he and his friend had been caught in the act of stealing. The rest of the conversation is lost to me, so confused by his manner was I that I doubted for a while that it was even my car. It went along the lines of me saying, “Move away from my car”, and him answering, “Yeah right, …f**k off!” This went back and forth a couple of times, whilst the kneeling man working at the bike rack. Confusion quickly turned to fear when the man who had been busy freeing my bike rack rose, turned and moved towards my right. I had no idea as to what tool he had in his hand and realised that my fear was fast becoming uncontrollable. I was unable to make any rational decision. I was aware that I should be doing something when the man leaning on the boot made the decision for me by flicking his cigarette at me. As soon as it left his fingers, he leapt at me. I stepped toward him and punched him twice in the face, knocking him backwards on to the bike rack.

There was a blur of movement to my right. My arm shot out and I contacted the man with the tool’s arm. I heard a crack and experienced a flash of light behind my eyes. I think that he overbalanced, as I was able to step closer and began punching as fast and as hard as I could. I have no idea where or how many times that I hit him, but I know that he hit me at least four times, very hard! He slipped again and staggered backwards. I could see his head and managed to land a few clean blows that had some effect. He continued to stagger backward until he fell into a low hedge in the flowerbed that ringed the car park. As he thrashed around, trying to regain his feet, I was able to repeatedly punch him hard in the stomach and groin. The weight of his body, coupled with his frenzied movement, caused him to break through the branches, and he fell into a sitting position within the hedge. Although he could still raise his hands, there was little that he could do to stop me from punching him in the face. I knocked him into a stupor, then stepped back and stomped on his ankle.

I spun around, expecting his friend rushing toward me, only to see that he was shuffling around, still at the rear of my car, reaching around to his back. I walked over to him, shaking and with no idea of what I was about to do next. As I got to within striking distance, I saw a man running towards us, shouting. I had no idea what he was saying, only that he was waving his hands around, but showing no signs of aggression. His behaviour distracted me and I lost all interest in pursuing the fight. I was physically spent and thoroughly exhausted. Despite an extremely high level of fitness, all my energy had been used up in a few short seconds. The fight was over, the whole thing not lasting more than a minute. I did not sleep well for a couple of weeks after that, I was profoundly disturbed at my inability to handle the situation. In the aftermath, I replayed the scenario repeatedly in my mind, in an effort to better understand how I could have coped with the situation more effectively, and tried in vain to rationalise my fear.

I came to realise that after years of studying the martial arts, I had yet to learn how to control my fear, and that without the ability to control my fear, I was destined to relive and replay my mismanagement of the situation over and over again. I had been involved in many fights before this one, yet I had never suffered the resultant disruption to my thinking or emotions. What seemed to separate those encounters from this one was the need for tactical positioning, a skill that I obviously lacked. This, coupled with the behaviour of the men involved, triggered a progressive evolution of thinking that I was completely untrained to deal with.

Andrew Williams

Emotional Control

Fear is the most overlooked aspect of any attack scenario. That is to say, those who overlook or pay little attention to this aspect of a fight could not have experienced an attack themselves, or are unwilling to admit to feeling fear. Fear leaves one of the most lasting impressions after an attack. The memories and biochemical residues are powerfully evident and profound. The creation of fear in the victim is one of the major goals and weapons employed by a would-be attacker. As such, any self defence system that ignores or plays down this aspect cannot be regarded as realistic. In fact, martial arts instructors who teach self defence tactics that are repetition/technique based, executed on overly compliant partners, and do not take into account the effects of fear in a life or death scenario, are possibly placing their students in a dangerous position. When in a critical situation where fear is a factor, the student can end up with a “log jam” of techniques and find it difficult to apply the appropriate response as well as deal with the physical and emotional effects of fear. This type of techniques based training can also develop an “arm lock” mentality. An example of this occurs when the martial artist tries to fit a technique into an inappropriate situation.

It is interesting to note the lack of understanding displayed by some instructors where they suggest things like “fight like a tiger” or “have the courage of a lion”. This simplistic approach is ignorant at best and extremely dangerous if the student believes that by simply thinking that he/she is a savage beast he/she will magically adopt the level of courage and fighting prowess attributed to the animal.

The attacker uses fear as a weapon. We will aim to rationalise fear and thereby go some way towards negating its influence on the outcome of an attack. In fact, when encouraged in the right manner, one can learn to harness their own fear bio-chemical responses and effects to great personal benefit. Proper consideration should also be given to the control of anger. Aggression can be a useful tool when channelled correctly. However, anger is a sign of a lack of mental control and can blind you to what is going on around you, affecting your own intuitive responses. Needless to say, if there is more than one attacker, you need to be conscious of all that is going on around you. If you are not aware, you increase your chances of choosing an inappropriate action which may have disastrous results if the people with whom you are dealing are serious in their intentions to do you harm.

Control over your emotions is also required if your situation has deteriorated and your fear has become completely invasive. It is useful in such situations to be able to focus your thoughts around an image that will give you the determination not to give in or surrender to your fears and therefore the attack. For example, if you have been knocked to the ground and your thoughts are in disarray and fear is taking control, you could use this image to help crystallise your thoughts, a thought that would prompt you to act, to fight on, or to take flight. It should be an image which has strong meaning for you and one which gives you cause to take action.

What is Effective Personal Protection?

At the core of any good personal protection system are one or two techniques, at most a handful, honed and developed using the principles of simplicity, directness and efficiency. Given the opportunity, these techniques should be applied with the intention of being first, being fast and being ferocious.

Be honest and ask yourself if your system fits these criteria, and if it doesn’t, then maybe it’s time to reassess your approach to Personal Protection. Consider the following definitions:

It is the ability to constantly monitor your surroundings that affords you the greatest level of protection from attack. As with most things of value, the functional levels of protective awareness take time and effort to develop.

Colour Coding

One technique that can be used to help develop a better understanding of the different levels of awareness is a visualised colour system. Such systems have been utilised with great success in combat pistol instruction and are easily applied in the realms of self-protection. It is also a system that Thompson and Consterdine have tailored to suit their own protection method and has proved inspirational in the development of our model.

The colour guide can be seen as an ascending ladder (see next page) and has been prepared to help readers to understand the various levels of awareness, or the “colour condition” that they are in, in relation to a threat, the form and content of these threats, and the likely consequences.

Levels of Awareness (in summary)

Condition White: Condition White can be seen as the level of awareness that is dangerously low. Unfortunately, it is the condition occupied by most people most of the time. To be in Condition White means that your chances of being aware of any threat to yourself are greatly reduced. The resulting inability to perceive a threat, for example, as a result of being mentally distracted, will dramatically increase the chances of being taken by surprise, with little or no chance of avoiding an attack or issuing a counter-attack.

Condition Yellow: By developing a calm, subliminal awareness, not paranoia, you will be aware of a change in the environment and have time to adjust. Being “quietly alert” is another way of putting it.

Condition Orange: When a change occurs and you are aware of it, you give yourself a chance to avoid or counter a threat. In practical terms, you will be able very quickly to evaluate the threat and put in place strategies and tactics to avoid or otherwise deal with the threat in an effective and efficient manner.

Condition Red: Fight or Flight the moment of truth. If you have to fight, be first, be fast and be ferocious. It is far better to be pro-active than reactive. Seize the initiative before it is too late.

Visualisation

It can be useful to get a visualisation of the awareness levels in your mind, using the colour code as outlined above. When applied correctly, this will enhance your decision making process.

NB: Condition Red must not be visualised as, say, a red flashing light overlaid with words like “emergency” or “battle stations”. That would presuppose that there is still time left to prepare for action. Instead, Condition Red should be seen as an automatic, virtually instant trigger for full blooded, totally committed action.

Levels of Awareness (in detail)

Condition White – Having little or no awareness

Attack can take numerous forms, eg.:

Condition Yellow – Forming A Basis for Personal Security

To attain Condition Yellow, you need to have developed a subliminal level of awareness (it must be stressed that this is not to be confused with a sense of paranoia). Subliminal awareness can be developed in a number of ways, however the most accessible of these is a standard technique used in training advanced tactical drivers. It is called “commentary driving”, and is a procedure whereby one has a conscious recognition of the changing environment. The same can be done whilst walking. The idea is to verbalise your changing surroundings as you move along, noting as many things as possible, such as the traffic conditions, weather, scenery, people in your environment, areas that could be used for concealment, and so on. By using this simple technique, and depending on your seriousness, it can take from one to four weeks to develop a conscious, continuous and accurate recognition of your surroundings. Once this is done, there is no need to verbalise anything, it will occur naturally on a subliminal level.

There are a number of complementary drills which can be used to develop and enhance your subliminal awareness. These include:

Threat Awareness

Threat Evaluation

Threat Avoidance

It is important to note here that a tactical evaluation is only valid if the appraisal of your part in the scenario is realistic and honest.

At this stage, it may still be possible to walk away from the threat or danger, and Threat Avoidance may be your best option. However, you may not be able to control the situation and may find yourself in a position where your level of awareness is heightened to Condition Orange.

Condition Orange – Threat Escalation / Making the Decision

This is in some respects the most crucial condition that you will find yourself in. Having come from the personal security basis of Condition Yellow, with the understanding of threat awareness, evaluation and avoidance, you are now faced with making the decision!

Threat Evaluation and Avoidance

This is a tactical situation and requires a critical assessment. If your training has led you to believe that you will somehow be able to control yourself and the situation without your training ever having placed you in harm’s way, then you have been misinformed. To truly understand how the pressure of a confrontation (or the potential of a confrontation) can effect your decision-making process, you need to duplicate the pressure in the dojo or kwoon. There are vast differences between sparring in an institution where you know that a fight will not deteriorate to the point where your opponent is going to bite you or stab you after you are knocked to the ground, and when these things become a very real possibility.

Psychological Tactics

Attackers often perform patterns of behaviour before they commence their assault. If you can identify these patterns you may even be able to implement your own psychological tactics and gain better control of the situation.

Whether they know it or not, your attacker will probably employ one of the following ploys when approaching you:

1. Disarming / Deceptive (eg. asking for the time or directions, etc.) When using this ploy your attacker is not only trying to lull you into a false sense of security, but also attempting to draw your attention away from his “line up” (ie: his intentions, and the position/posture from which he intends to launch his attack). If successfully executed, where you are taken by surprise, the effects can be devastating. Not only will you be unprepared physically for the attack and most likely receive the full brunt of the blow, but, more importantly you will be unprepared emotionally. Here, fear is your enemy, and to now be able to bring the resultant rush of adrenaline under control will be extremely difficult. There are, however, methods of training that can bring about the spontaneous control of adrenaline and, consequently, you will be more able to fight from this disadvantageous position.

2. Aggressive (using verbal and/or physical threat behaviour) There are many ways to display aggression. Understanding patterns of behaviour is extremely important. Verbal aggression (whether your attacker understands it or not) is a means whereby your attacker can engage your mind, resulting in a multitude of effects. These range from a general feeling of unease all the way through to blind panic, thus disabling one’s ability to react instinctively. Physically threatening behaviour is perhaps the most frightening and potent weapon that the attacker can employ. While many of us have been in a verbal argument, most people have not experienced the type of physical contact that may be a precursor to a full-blown assault.

Of course we can talk about how we could cope with such a situation, but unless you practise and develop strategies to deal with physical and verbal abuse as part of a pre-fight ritual, your skill in dealing with this scenario will be lacking. The fight can be won or lost before the first punch is thrown, yet this often discussed aspect of fighting goes largely unpractised. For instance, how do you maintain the optimal distance to launch your own pre-emptive strike without moving into kicking or grappling range? How do you maintain a tactile reference that allows you to subtly monitor your assailant’s intentions as well as controlling a bridging arm? If there is more than one attacker, how do you maintain or even attain a superior tactical position if your attackers are not compliant and/or mobile and aggressive? The answer is probably, “You cannot!”, unless it is a skill that you have developed and practised under pressure. Another idea to keep in mind is that you can gain some understanding of your enemies fears by recognising the means he uses in an effort to frighten you.

Armed and Aggressive

If it were suggested to you that the opponent you were about to face was carrying a concealed weapon, that the attacker had every intention of using the weapon (let’s say that he has a butcher’s boning knife), do you believe that you would then proceed in a similar fashion as you would if you were in ignorance of the weapon? You would be well advised to treat every attacker as armed, whether a weapon is in evidence or not.

Have you been in a threatening situation where people around you were unknown to you? If a fight had started could you discount the possibility that those around you would not join in with an attack against you? Just as weapons can be concealed, so can your potential assailants. Treat every attack as a multiple attack.

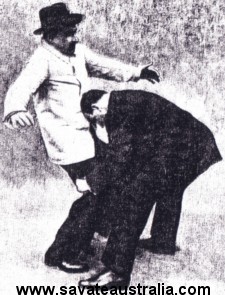

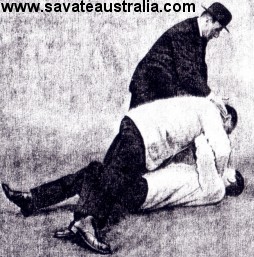

The above would suggest that fighting should be avoided because of the incalculable and hidden variables, however if you have to fight you should dispatch your attacker(s) as vigorously and quickly as possible, with little remorse. Avoid going to the ground because once there, it is difficult to get up if you are outnumbered. There is now a huge increase in the popularity of grappling arts. There can be no doubt as to their effectiveness, but arts that seek to take their opponents to the ground at the earliest opportunity may place the practitioner at a disadvantage, especially if those who are attacking them are prepared to do so with absolutely no consideration for gentlemanly fair-play, and no regard of the consequences.

Remember, any tactic that the assailant uses is designed to engage your conscious thought process. You are left vulnerable if this is allowed to happen and must guard against such tactics. By being aware of these psychological tactics you can also employ similar and additional counter tactics to engage your attacker’s thought processes. You too can be:

The methodology of Fear Control which is presented below is based on experience and research, and we would encourage the reader to research their own experience, and that of their peers, openly and honestly. Central to any discussion of the response to a perceived threat is to understand the physiological responses that the body has when a potential menace is recognised. One of the first things to realise is that your thinking stimulates the physiological reaction, and that it is your own thinking which can therefore control and harness this response. “Fear is in the mind of the beholder.”

Fear is experienced as a sudden release of adrenaline (a combination of two chemicals, Epinephrine and Norepinephrine), followed immediately by the associated physiological responses. If left uncontrolled, these responses can have a devastating effect on both the body and the mind. Most of us have been conditioned to associate the effects of these adrenalines with fear, rather than as a means of providing a biological “overdrive”, commonly referred to as the “fight and flight syndrome”.

Fear can be thought paralysing, causing one to act irrationally, or not to act at all, thus giving the attacker a devastating advantage, ie. the ability to attack you without fear of reprisal. To learn how to control fear, one must confront fear, to move outside of one’s comfort zone. This can be done through the creation of a Fear Pyramid, whereby you confront your own fears, starting with the mildest at the bottom of the pyramid, and working up to your worst nightmare at the top.

The idea is not to rid yourself of fear per se, but to get used to or desensitised to its harmful effects on you and instead learn how to harness their effects and make them a useful tool. As already mentioned, fear is merely a biochemical reaction to a perceived threat. It can in fact heighten your awareness as well as prepare your body for action. These are useful reactions to have under control. A requirement of a more complete training regime would be to acclimatise its participants to the effects of adrenaline, and if structured correctly, slowly condition the students to make effective use of it’s effects, some of which are:

March 1998

As a professional Fire Fighter you come to expect the unexpected. You might be “turned-out” to a yard fire and on arrival find a house fully involved with fire and people trapped inside. And so it was in March of 1998 when, at approximately 1.00am, the crew of Canning Vale Fire Station’s Pump and Light Tanker were turned-out to a grass fire on Chapman Way in Canning Vale. I was the passenger in the Light Tanker, which is a Toyota Landcruiser fitted with a rear-mounted 650 litre water tank specifically designed to suppress grass and scrub fires. The Light Tanker follows the larger Pump, a 12 tonne Scannia, in which sit an officer and driver.

When we arrived at Chapman Road we found a street party taking place, involving some 1600 people, mostly young men, most of whom appeared intoxicated. The Officer in the leading vehicle decided that we had best leave the area as the partygoers were clearly upset by our presence. It was quickly obvious that we would be ill advised to attempt to reverse or u-turn in order to quit the area, the road being too narrow and lined with partygoers cars, plus the ever increasing presence of the now agitated partygoers, so we came to a halt.

Some 50 metres in front of us was the main body of the crowd who were, as yet, unaware of our presence, despite the fact that our vehicles were slowly being surrounded by a gathering crowd which was decidedly unfriendly. With no police present, our options were severely limited, so the Officer in Charge communicated over the radio that we should push gently forward through the crowd to escape the area. As the Pump started to move forward a small fire was lit in the grass next to our vehicle. The summer had been long and hot, with many days reaching temperatures in excess of 40 degrees Centigrade, and even small fires had the potential to quickly develop into something that threatened life and property. There was no way that Phil, my driver, and I could ignore the fire, so we stopped and exited the Tanker.

The fire was indeed growing in size, and people had started to push back from the fire’s edge. The hose-reel for the Tanker is attached to the rear of the truck, so Phil and I had to push and shove through the crowd to get to it. A small band of men had taken the branch (ie. the nozzle) and were running the hose down the road. Up until now the crowd had done no more than hinder our progress and be slightly abusive, but at this point I felt that they now believed that we were going to interfere with their fun, and their behaviour became noticeably more aggressive. I looked back towards the fire, which had now grown to a threatening size, and with an increased sense of urgency, I began to pursue the group with the branch and hose up the road, leaving behind the crowd around the Tanker.

A small group of young men stepped out from between a row of cars and blocked my path. I had no time to waste so my intention was to push through them in an effort to regain the hose. They did not break ranks as I neared, but instead stepped towards and around me. Without a word they started throwing punches, some of which landed, but most of which bounced off harmlessly. My only reaction was to remain calm, show no fear, and make a determined effort to regain the hose and branch. After the initial onslaught of blows, a couple of the guys stepped back. I could not tell you what they were thinking, but they did look surprised. I told them to move out of the way and pointed back at the fire, which had now started to cross a paddock and run towards a house. I asked them if it was their intention to let the house burn down. This had the desired effect as I was then able to force my way through their tight cordon.

There was much the same reaction and action when I got to the group with the branch, but I did finally manage to retrieve it, run back to the fire and extinguish it. Whilst doing that I was assaulted twice more, but my only real concern was to make sure that the house and the people inside it were not placed in any further danger. The crowd gathering around Phil and me had swelled to a point where I could no longer see the Pump’s position. A few of them now started to throw bottles and Phil had to take cover in our vehicle. I was cut off from the Tanker by another group who “got stuck in”. At least when that was happening, no one threw bottles at me.

As I forced my way back to the Tanker, I saw that there was a large number of people pulling equipment off the Pump, some of which is extremely expensive, most of which is essential to our job. I yelled at Phil to follow me to the Tanker, and on foot I pushed towards the people with the equipment. I managed to wrestle some of it back, but by now there was a veritable storm of bottles raining down on the Tanker and myself. This forced most of the crowd back when a couple of them were hit by “friendly fire”. It was definitely time to get out. Phil had a broken bottle pushed through his window, narrowly missing his face, but he remained calm and drove at a pace that matched my walking. We forced a way through the crowd to the other side of the party, not wanting to stop and present a stationary target, and finally passed through this gauntlet which was some 200 metres long. We returned to the station and I was then off to hospital. Thankfully the rest of the crew were physically unharmed

Why didn’t I retaliate? Why hadn’t we turned our hoses on the crowd? Why didn’t we drive our vehicle into the densely packed people? Discipline! I was mentally aware through the whole affair but at no stage did I behave or think recklessly. I controlled and used the adrenaline rushing through my body. I remained calm so as not to provoke any retaliation from the partygoers and further expose Phil or myself to danger.

Had we not behaved in such a disciplined fashion, it is my belief , and that of the men I work with and the police investigating the incident, that the repercussions and retaliation we could have suffered would have been far greater. Phil later told me that he had been terrified, but had taken strength from my apparent calm and control, both of which I have developed within the confines of a martial arts club. By training in a realistic manner, which is pressure filled, my ability to cope is constantly strained and tested. It is because of this that I have been able to master some of my demons and am now on the long path to beating my “Inner Opponent”.

Andrew Williams

Responses

If you allow your attacker to initiate the action then he will usually dictate your response. This will allow him to determine the distance at which the altercation will take place, and this may not be the distance where you can best apply your protective principles. Many arts now talk of “bridging the gap” or “making distance”. This may be relevant in a match fight or an organised competition, but in the street, if your attacker wishes to truly hurt you, he will have to close the distance to where he can best dictate the terms of the altercation. Thus it is imperative that you know how to deal with your attacker at kicking or punching range because if you cannot, the fight may then go to grappling range and once there it would be almost impossible to return to any other range. The implementation of a decisive posture will help to maintain your preferred distance and enable you to position yourself whereby you can launch a pre-emptive strike. Given the right sort of training, this tactic will finish the fight instantly. You need to place yourself in a position that offers little option of attack for your opponent, yet allows you to “line up” on him, positioning yourself so that you can achieve your objective without exposing your intention.

Your “line up” will influence:

How you can, and will respond, will very largely be dependant on your posture when confronted by your attacker. To effectively “line up” your opponent requires a decisive posture. Whether the fight is won or lost may well be determined by the posture (physical and mental) taken in the lead up to the altercation. Effective components of a decisive posture, that allows for the option and delivery of a pre-emptive strike, include all of the following:

Condition Red - Action!!!!

The threat is unavoidable, …it is now “the moment of truth“. Using a “trigger for action”, which might be a verbal prompt, or even your own decisive posture, and given the opportunity, you should apply the acceptable option of the pre emptive strike. For the pre-emptive strike to be pursued successfully, one would need it to be applied with what is commonly described as “extreme prejudice”. In training the emotional wherewithal to do this, it may help to keep in mind this mantra:

BE FIRST

BE FAST

BE FEROCIOUS

It is absolutely essential that you totally overwhelm your opponent and that you deliver your attacks with the sort of venom which will ensure this aim. If the fight is on, if not totally committed to the attack being launched, you are destined to become the victim rather than the victor. Is there a component in your training that achieves this? Do you train in a fashion that places you in the frame of mind that allows you to feel the discipline and commitment that encourages you to “win at all costs”, lest you suffer the consequences? To this end, it is crucial that you make all drills, including striking practice, take on a reality that approximates the realism of the street. While attacking the striking pad or punching bag, role play the scenario, get into the right frame of mind, and EXPLODE when the strike is launched. In addition to the above, make sure that your practise sessions only make use of techniques that are:

SIMPLE

DIRECT

EFFICIENT

Multiple Attackers

Just as every attacker should be dealt with as if he were armed, so too should every attack be dealt with as if it has the potential to become an attack from more than one aggressor. This reason alone would determine that grappling or “going to the mat” should be avoided at all costs on the street. Psychological tactics, decisive postures and emotional control should still be employed, but you must quickly recognise the attacker who presents the greatest threat to you. He is the person you should deal with first. It may not always be the largest of your attackers who represents this threat. It is the person who can strike you the quickest and with the least amount of potential resistance or reaction from you. This again illustrates the need to develop devastatingly powerful blows, and a system to deliver them. If you do not drop your man quickly, no amount of ‘Chi Sau’ will enable you to cross arms with multiple attackers. Thompson and Consterdine refer to their management of this situation as dealing with the “red letter syndrome“. The bill that represents the greatest threat to you, eg. to cut off your electricity supply, is the one printed in red. It is the red one you deal with first.

Just as one cannot expect reasonable levels of improvement in the haphazard application of a physical training regime, one cannot expect credible results from the random implementation of emotional training. The instructor needs to consider the emotional needs of each student and construct and implement a flexible training model. Students of the martial art of Wing Chun are uniquely placed to take advantage of the concepts of Personal Protection. They are already practising a martial method dedicated almost exclusively to fighting. The followers of the “Wong Shun Leung Way” of Wing Chun have a distinct advantage in having, as their mentor, a man who pioneered a method based upon his experiences in countless real life fights. He brought these experiences into every aspect of his Wing Chun teaching, advocating the injection of a great deal of realism into his training sessions and seminars. Most importantly, sifu Wong advocated the natural application of internalised physical concepts and a flexible approach to “in-fight thinking”, rather than the rote learning of set techniques or responses, as is in evidence to anyone lucky enough to have trained with him. Thus, his teachings easily lend themselves to the Personal Protection concept, and vice versa.

Martial artists of other disciplines would do well to look at their own approach to self protection and ask themselves what they could do to make their methods more street effective. It takes more than flashy techniques to survive a street encounter. What is needed are sound concepts, effective and realistic training methods, and a complete understanding of the psychology of the attacker, as well as oneself. We need to conquer, or at least begin to recognise our fears, to gain control of our emotions, to develop threat awareness and how to deal with it effectively. As Sun Zi wrote in his celebrated “Art of War” over 2000 years ago,

“Know the other and know yourself:

One hundred challenges without danger;

Know not the other and yet know yourself:

One triumph for one defeat;

Know not the other and know not yourself:

Every challenge is certain peril“.

It is, or should be, the goal of every sincere instructor to equip his or her students with the skills to survive. It is the wish of the authors of this article to encourage, at the very least, a discussion of the protective methods now employed in your school. We would hope that the concept of Personal Protection presented on these pages will lead to a return to reality and practicality in the martial arts, regardless of style. Good luck in developing your potential, and that of your students!

About the authors: Andrew Williams has trained extensively in two different Wing Chun systems, had his skills tested in numerous real life encounters, and is fast being recognised as an innovative Wing Chun instructor. Williams is currently assisting Rolf Clausnitzer of the ‘Wing Chun Academy of Western Australia’. Clausnitzer was the late Sifu Wong Shun Leung’s first foreign student and co-author (with Greco Wong) of the first ever English language introduction to Wing Chun. David Peterson, principal instructor of the ‘Melbourne Chinese Martial Arts Club’, has been publicly acknowledged by Sifu Wong as one of his outstanding overseas students/instructors, acting as Sifu Wong’s personal translator during five seminar tours to Australia. Peterson is also a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in many Australian and international journals, and more recently, on several Internet sites around the world.

It is inspired by and based on two major influences:

1. The work done by two very respected and experienced (in terms of both tournament performance and real life confrontations) British martial artists, Geoff Thompson and Peter Consterdine; and

2. The highly efficient and practical Chinese martial art of Wing Chun Kuen which, interestingly, Messrs. Thompson and Consterdine acknowledge in their video series, “The Pavement Arena”, as having had a major influence on their own self protection philosophy and methods.

Wing Chun is a major Chinese martial art or system that is unparalleled in its suitability for today’s urban environment. It is radically different in its general approach from that of most traditional martial arts, as it is not reliant on strength, balletic poise, acrobatic movements, or a complexity of often flamboyant techniques. Instead of being technique oriented and requiring students to learn by rote an endless variety of movements (which often result in a mental “log jam” in real life situations), Wing Chun is based on a clear understanding of fighting concepts and strategies, expressed via a minimal number of techniques which meet the basic criteria of simplicity, directness and efficiency.

Although widely believed to have been founded and developed by a Buddhist nun, Ng Mui, and her female pupil, Yim Wing Chun, about 200 hundred years ago, Wing Chun has evolved over time via a process of “natural selection”, with a continual discarding of superfluous, complex and ineffective techniques and movements. It is the system that the legendary Bruce Lee used as the foundation of his own combat philosophy of Jeet Kune Do, and has become the most influential style of Kung Fu, allowing even traditional Karate and other Kung Fu practitioners to reappraise and enhance their own skills and techniques.

Successfully tested in real “no-holds barred” fights against numerous other styles in Hong Kong in the 1950′s and early 1960′s by outstanding students of Grandmaster Yip Man, such as the late Sifu Wong Shun Leung and Sifu Wang Kiu, Wing Chun is considered to be one of the most, if not the most practical and efficient martial arts for use in today’s increasingly violent environment. In simple terms, Wing Chun is the “Science of Street Fighting“, designed solely for the purpose of surviving an attack by being a better attacker than one’s assailant. Hence it forms the perfect basis for the concept of Personal Protection.

It should be made clear at the outset that this document is only a basic guideline, not intended to be, or taken for, a comprehensive and definitive work. For example, it does not purport to supply the reader with an in depth examination of an attacker’s psychology. Nor is it a typical “how to” manual, detailing specific, complicated self-defence techniques in make believe, often unrealistic situations. It is certainly not intended to lead the reader through a sequence of events culminating in the inevitable limiting solution.

It is the sincere wish of the authors, however, to encourage readers to take a closer and more realistic look at the concept of personal security, a good understanding of which, under the guidance of an experienced and competent instructor, can provide a sound basis for developing a practical and effective method of self protection. It should be stressed, of course, in view of the complexity of the subject, that this article is not to be taken as a “quick fix”, ready-made set of rules for instant implementation. Considerable analysis, discussion, and testing are called for, as any one of the main ideas or principles outlined could itself become the theme for an entire seminar. Further, a particular idea may not automatically fit in with your philosophy of fighting or it may need to be modified accordingly.

It should be pointed out at this stage that, as few of us can rely on great physical strength, it is vital that the instructor has a clear understanding of power generation utilising an informed understanding of exercise methodologies and biomechanics, thus enabling the students to realise their full striking potential. An open mind is called for, far removed from the “arm lock” mentality* of many martial arts systems, not only to get the most out of the concepts presented in this paper, but also to get the best out of those inherent in all martial arts.

Personal Protection is not a sport, but a serious approach to preparing oneself for potential real life threats. To quote an ancient Chinese sage, Li Chuan, “War is a grave matter. One is apprehensive lest men embark on it without due reflection”. A skilful fighter is one who is able to triumph over his or her opponent by having a deep understanding of their own capabilities and potential. Therefore, the proper training is essential, training that prepares you not only physically, but mentally and emotionally as well.

As stated at the beginning of this article, Personal Protection is certainly a departure from the countless “self defence” instruction methods, widely depicted, showing attackers in unrealistic, static, even clumsily inept poses, telegraphing their movements, and “allowing” themselves to be handled with impunity by the defender. And it is certainly not an exploration of the dramatic scenario so popular with idealistic and inexperienced instructors in countless martial arts clubs around

the world, where the two antagonists conduct a gentlemanly bout to decide who is the better man, two noble warriors observing a set of rules and a pattern of ritualistic behaviours, who by mutual consent begin a dignified exchange of technique.

*ie: the mentality that many martial artists exhibit, in that they will try to make a technique fit the situation (eg: try to put their opponent in an arm-lock), no matter what, becoming, in the words of Master Sifu Wong Shun Leung, “…a slave to their art, instead of a master of it”

In the street, the classical depiction of a defender representing a particular martial art squaring off against an attacker from another system is seldom, if ever, encountered. Violence can erupt with little or no sign of threat. And this eruption is usually in the form of a vicious, spiteful act, carried out with deadly intent, with no regard for the rules of civilised conduct and little, if any, resemblance to the set piece duel in the dojo or kwoon. In the street, almost every conceivable weapon, from keys and cutting weapons to baseball bats and house bricks, is used to inflict pain, serious injury, and even death. And it is here that you are more likely to be savagely bitten by a crazed attacker than to be stopped by a beautifully executed roundhouse kick to the head.

It should also be noted that few of us these days have the “luxury” of testing our fighting skills in real combat situations. As such, we are usually unable to duplicate the enormous amounts of emotional pressure that accompany a real fight in the practise of sparring or ‘Chi Sau’. Both lack the physical and verbal aggression so often used by remorseless street opponents.

PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

Attack ScenariosMost acts of violence and physical abuse are carried out in familiar surroundings, by people one knows. They can be long term, and often occur in the home, perpetrated by a family member or so called friend, and if you are unable or unwilling to confront these cowardly individuals, your best long term defence is to use the laws that are in place to protect you.

Not all attacks, however, occur in the home and not all the perpetrators are known. They are usually carried out by vicious, cowardly individuals and/or people seeking monetary gain. It has been said that 99% of these attacks are opportunistic, ie. they are not pre planned but occur at the time because the “conditions” seem right to the attacker(s).

Environmentally, there are two “basic” ways in which you may be attacked. Firstly, your attacker can strike suddenly from a concealed position, utilising the element of surprise. The object is to catch you unawares and subject you to enormous pressure, mentally, physically and, most importantly, emotionally. The sudden change in your emotional state is effected by the body’s reaction to threat, which is normally experienced as fear. If this reaction is uncontrolled, you will limit or waste your chance to react or retaliate in an effective manner, whether that is to run or to stand and fight. The attacker can use a multitude of situations in which to stage an ambush. This would of course dictate that one needs a highly developed sense of subliminal threat awareness in order to minimise the possibility of being attacked and/or surprised. As it is improbable, however, that one could remain vigilant all of the time, the next best option is to train in such a way as to develop a high degree of control over your body’s reaction to threat. This type of instruction requires a high degree of realism and honesty within your training regime, never accepting a protective technique just because it looks like it would or could work. It requires the continual testing of the limits of your emotional capabilities in a threatening and violent environment.

Another method of attack would be for the opponent to confront you at a very close range, employing psychological tactics. Your attacker needs to be close so that you feel the full force of their aggressive tactic. These tactics can vary greatly, but their underlying purpose is to engage your thought processes and hence control your corresponding emotional reactions in some way, to make you more vulnerable to attack. As in the ambush scenario, fear is a major weapon in the arsenal of the attacker, who may adopt aggressive tactics, where prodding, shoving, abusive and threatening language, and menacing, threatening gestures may all be utilised to create fear and even panic. On the other hand, the attacker may decide to adopt the very different strategy of appearing to be non-threatening, by behaving in a disarming and deceptive manner. He may ask you a seemingly harmless question designed not to upset you, but to distract you in some way, thereby making you vulnerable to a sudden attack because you are in a more relaxed state and off your guard. Here the attacker relies on the ability to launch his attack without you being aware of their intention, and again it is worth considering the distance this is best achieved from.

Distance Management

Amidst the endless variations and combinations of ambushes, surprise attacks, and openly aggressive assaults, it is very important to bear in mind that it is nearly always the attacker who dictates (or intends to dictate) the physical distance at which the confrontation and assault will take place. It is somewhat ludicrous to believe that this distance is the one usually depicted in martial arts movies, or the regimented distance at which sporting competitors begin their exchanges in tournaments. In reality, it is the distance where the victim can be struck with little warning and the full impact of an aggressive approach can be felt. It is the distance where one may engage another in polite conversation, or to stop to ask for directions or the time. The distance is almost, without exception, punching, kneeing, headbutting or stabbing distance. It is only logical, from the attacker’s viewpoint to utilise this range. Afterall, why would you allow someone to have the room to manoeuvre or recognise your initial movement to strike them?

If you accept this notion, and from our personal experience, and from the related experiences of our peers, we believe it to be true, and if you are serious in your intentions to teach or learn practical self-protection, then this is the distance you will base most, if not all of your training strategies, tactics, and power development drills for Personal Protection. It would require enormous discipline to remain fully aware all the time, and the nature of most societies would make it almost impossible to maintain a personal safety area that would inhibit an attacker’s intention to get within striking distance, so the ability to recognise ritualised patterns of assault behaviour is essential.

The Victim Syndrome

On their videotape entitled “The Pavement Arena”, Geoff Thompson and Peter Consterdine say that a booby trap or bomb is deemed to be victim operated. So it is that in many instances an attack on yourself can be said to be victim operated. You can make yourself a victim by your lack of awareness, your meek demeanour and other body language. Once you understand, and more importantly, practise the concepts and strategies of Personal Protection, however, you will be able to project a more positive and confident image. It will enable you to become more aware of someone’s intention to attack you. Put yourself in the attacker’s position, …whom would you attack? Someone who presents a formidable target, or a person who looks like a pushover?

December 1993

I had to return to my car in the dark. The area was renowned for being dangerous at night and I was nervous to be alone. I walked on the footpath close to the road and watched each door and alleyway for movement. I walked into the car park and kept close to the middle of the driveway lest someone was waiting in ambush. I would look over my shoulder as a matter of routine whilst maintaining a steady, even pace. I was about twenty metres from my car when I could make out two people near where I remembered parking my vehicle. As I drew closer, I could see that they were at the rear of my car. One man was crouched and was busying himself with my bike rack which was attached to the car’s tow-bar. The other guy leaned casually on the boot of my car, smoking a cigarette. I was about five metres away when the smoking man became aware of me, and he looked in my direction and said, “G’day mate.”

I was shocked. He seemed so casual and displayed no concern that he and his friend had been caught in the act of stealing. The rest of the conversation is lost to me, so confused by his manner was I that I doubted for a while that it was even my car. It went along the lines of me saying, “Move away from my car”, and him answering, “Yeah right, …f**k off!” This went back and forth a couple of times, whilst the kneeling man working at the bike rack. Confusion quickly turned to fear when the man who had been busy freeing my bike rack rose, turned and moved towards my right. I had no idea as to what tool he had in his hand and realised that my fear was fast becoming uncontrollable. I was unable to make any rational decision. I was aware that I should be doing something when the man leaning on the boot made the decision for me by flicking his cigarette at me. As soon as it left his fingers, he leapt at me. I stepped toward him and punched him twice in the face, knocking him backwards on to the bike rack.

There was a blur of movement to my right. My arm shot out and I contacted the man with the tool’s arm. I heard a crack and experienced a flash of light behind my eyes. I think that he overbalanced, as I was able to step closer and began punching as fast and as hard as I could. I have no idea where or how many times that I hit him, but I know that he hit me at least four times, very hard! He slipped again and staggered backwards. I could see his head and managed to land a few clean blows that had some effect. He continued to stagger backward until he fell into a low hedge in the flowerbed that ringed the car park. As he thrashed around, trying to regain his feet, I was able to repeatedly punch him hard in the stomach and groin. The weight of his body, coupled with his frenzied movement, caused him to break through the branches, and he fell into a sitting position within the hedge. Although he could still raise his hands, there was little that he could do to stop me from punching him in the face. I knocked him into a stupor, then stepped back and stomped on his ankle.

I spun around, expecting his friend rushing toward me, only to see that he was shuffling around, still at the rear of my car, reaching around to his back. I walked over to him, shaking and with no idea of what I was about to do next. As I got to within striking distance, I saw a man running towards us, shouting. I had no idea what he was saying, only that he was waving his hands around, but showing no signs of aggression. His behaviour distracted me and I lost all interest in pursuing the fight. I was physically spent and thoroughly exhausted. Despite an extremely high level of fitness, all my energy had been used up in a few short seconds. The fight was over, the whole thing not lasting more than a minute. I did not sleep well for a couple of weeks after that, I was profoundly disturbed at my inability to handle the situation. In the aftermath, I replayed the scenario repeatedly in my mind, in an effort to better understand how I could have coped with the situation more effectively, and tried in vain to rationalise my fear.

I came to realise that after years of studying the martial arts, I had yet to learn how to control my fear, and that without the ability to control my fear, I was destined to relive and replay my mismanagement of the situation over and over again. I had been involved in many fights before this one, yet I had never suffered the resultant disruption to my thinking or emotions. What seemed to separate those encounters from this one was the need for tactical positioning, a skill that I obviously lacked. This, coupled with the behaviour of the men involved, triggered a progressive evolution of thinking that I was completely untrained to deal with.

Andrew Williams

Emotional Control

Fear is the most overlooked aspect of any attack scenario. That is to say, those who overlook or pay little attention to this aspect of a fight could not have experienced an attack themselves, or are unwilling to admit to feeling fear. Fear leaves one of the most lasting impressions after an attack. The memories and biochemical residues are powerfully evident and profound. The creation of fear in the victim is one of the major goals and weapons employed by a would-be attacker. As such, any self defence system that ignores or plays down this aspect cannot be regarded as realistic. In fact, martial arts instructors who teach self defence tactics that are repetition/technique based, executed on overly compliant partners, and do not take into account the effects of fear in a life or death scenario, are possibly placing their students in a dangerous position. When in a critical situation where fear is a factor, the student can end up with a “log jam” of techniques and find it difficult to apply the appropriate response as well as deal with the physical and emotional effects of fear. This type of techniques based training can also develop an “arm lock” mentality. An example of this occurs when the martial artist tries to fit a technique into an inappropriate situation.

It is interesting to note the lack of understanding displayed by some instructors where they suggest things like “fight like a tiger” or “have the courage of a lion”. This simplistic approach is ignorant at best and extremely dangerous if the student believes that by simply thinking that he/she is a savage beast he/she will magically adopt the level of courage and fighting prowess attributed to the animal.

The attacker uses fear as a weapon. We will aim to rationalise fear and thereby go some way towards negating its influence on the outcome of an attack. In fact, when encouraged in the right manner, one can learn to harness their own fear bio-chemical responses and effects to great personal benefit. Proper consideration should also be given to the control of anger. Aggression can be a useful tool when channelled correctly. However, anger is a sign of a lack of mental control and can blind you to what is going on around you, affecting your own intuitive responses. Needless to say, if there is more than one attacker, you need to be conscious of all that is going on around you. If you are not aware, you increase your chances of choosing an inappropriate action which may have disastrous results if the people with whom you are dealing are serious in their intentions to do you harm.

Control over your emotions is also required if your situation has deteriorated and your fear has become completely invasive. It is useful in such situations to be able to focus your thoughts around an image that will give you the determination not to give in or surrender to your fears and therefore the attack. For example, if you have been knocked to the ground and your thoughts are in disarray and fear is taking control, you could use this image to help crystallise your thoughts, a thought that would prompt you to act, to fight on, or to take flight. It should be an image which has strong meaning for you and one which gives you cause to take action.

What is Effective Personal Protection?

At the core of any good personal protection system are one or two techniques, at most a handful, honed and developed using the principles of simplicity, directness and efficiency. Given the opportunity, these techniques should be applied with the intention of being first, being fast and being ferocious.

Be honest and ask yourself if your system fits these criteria, and if it doesn’t, then maybe it’s time to reassess your approach to Personal Protection. Consider the following definitions:

| SIMPLE: | does not require analysis or thought processing; is as automatic as blinking; does not require balletic poise; utilises the minimum number of movements. |

| DIRECT: | follows the shortest distance from point A to B; where possible, attacks the closest target with the nearest weapon. |

| EFFICIENT: | does not create targets for the attacker; has minimal effect on balance/stability; uses economy of motion, achieving the expected outcome with minimal expenditure of energy. |

THE PROTECTION LADDER AND LEVELS OF AWARENESS

Levels of AwarenessIt is the ability to constantly monitor your surroundings that affords you the greatest level of protection from attack. As with most things of value, the functional levels of protective awareness take time and effort to develop.

Colour Coding

One technique that can be used to help develop a better understanding of the different levels of awareness is a visualised colour system. Such systems have been utilised with great success in combat pistol instruction and are easily applied in the realms of self-protection. It is also a system that Thompson and Consterdine have tailored to suit their own protection method and has proved inspirational in the development of our model.

The colour guide can be seen as an ascending ladder (see next page) and has been prepared to help readers to understand the various levels of awareness, or the “colour condition” that they are in, in relation to a threat, the form and content of these threats, and the likely consequences.

Levels of Awareness (in summary)

Condition White: Condition White can be seen as the level of awareness that is dangerously low. Unfortunately, it is the condition occupied by most people most of the time. To be in Condition White means that your chances of being aware of any threat to yourself are greatly reduced. The resulting inability to perceive a threat, for example, as a result of being mentally distracted, will dramatically increase the chances of being taken by surprise, with little or no chance of avoiding an attack or issuing a counter-attack.

THE PROTECTION LADDER AND LEVELS OF AWARENESSCONDITION RED FIGHT OR FLIGHT THE PRE-EMPTIVE STRIKE CONDITION ORANGE RESPONSE TO THREAT MAKING A DECISION CONDITION YELLOW BASIS FOR PERSONAL SECURITY AWARENESS – EVALUATION – AVOIDANCE CONDITION WHITE LACK OF AWARENESS |

| THE VICTIM SYNDROME |

Condition Orange: When a change occurs and you are aware of it, you give yourself a chance to avoid or counter a threat. In practical terms, you will be able very quickly to evaluate the threat and put in place strategies and tactics to avoid or otherwise deal with the threat in an effective and efficient manner.

Condition Red: Fight or Flight the moment of truth. If you have to fight, be first, be fast and be ferocious. It is far better to be pro-active than reactive. Seize the initiative before it is too late.

Visualisation

It can be useful to get a visualisation of the awareness levels in your mind, using the colour code as outlined above. When applied correctly, this will enhance your decision making process.

NB: Condition Red must not be visualised as, say, a red flashing light overlaid with words like “emergency” or “battle stations”. That would presuppose that there is still time left to prepare for action. Instead, Condition Red should be seen as an automatic, virtually instant trigger for full blooded, totally committed action.

Levels of Awareness (in detail)

Condition White – Having little or no awareness

Attack can take numerous forms, eg.:

- Murder

- Rape

- Assault

- Robbery

- Abduction

Condition Yellow – Forming A Basis for Personal Security

To attain Condition Yellow, you need to have developed a subliminal level of awareness (it must be stressed that this is not to be confused with a sense of paranoia). Subliminal awareness can be developed in a number of ways, however the most accessible of these is a standard technique used in training advanced tactical drivers. It is called “commentary driving”, and is a procedure whereby one has a conscious recognition of the changing environment. The same can be done whilst walking. The idea is to verbalise your changing surroundings as you move along, noting as many things as possible, such as the traffic conditions, weather, scenery, people in your environment, areas that could be used for concealment, and so on. By using this simple technique, and depending on your seriousness, it can take from one to four weeks to develop a conscious, continuous and accurate recognition of your surroundings. Once this is done, there is no need to verbalise anything, it will occur naturally on a subliminal level.

There are a number of complementary drills which can be used to develop and enhance your subliminal awareness. These include:

- Peripheral awareness drills

- Photo retentive recognition drills

- Recognition of threatening body language (static and dynamic)

- Recognition of pre-fight rituals (verbal and physical)

- Victim recognition/threat evaluation drills

- Immediate threat recognition drills

- Development and testing of a pre-plan

- Development of acronyms, eg: ‘KEYS’

- Karefully

- Evaluate

- Your

- Surroundings

Threat Awareness

Threat Evaluation

Threat Avoidance

It is important to note here that a tactical evaluation is only valid if the appraisal of your part in the scenario is realistic and honest.

At this stage, it may still be possible to walk away from the threat or danger, and Threat Avoidance may be your best option. However, you may not be able to control the situation and may find yourself in a position where your level of awareness is heightened to Condition Orange.

Condition Orange – Threat Escalation / Making the Decision

This is in some respects the most crucial condition that you will find yourself in. Having come from the personal security basis of Condition Yellow, with the understanding of threat awareness, evaluation and avoidance, you are now faced with making the decision!

Threat Evaluation and Avoidance

This is a tactical situation and requires a critical assessment. If your training has led you to believe that you will somehow be able to control yourself and the situation without your training ever having placed you in harm’s way, then you have been misinformed. To truly understand how the pressure of a confrontation (or the potential of a confrontation) can effect your decision-making process, you need to duplicate the pressure in the dojo or kwoon. There are vast differences between sparring in an institution where you know that a fight will not deteriorate to the point where your opponent is going to bite you or stab you after you are knocked to the ground, and when these things become a very real possibility.

Psychological Tactics

Attackers often perform patterns of behaviour before they commence their assault. If you can identify these patterns you may even be able to implement your own psychological tactics and gain better control of the situation.

Whether they know it or not, your attacker will probably employ one of the following ploys when approaching you:

1. Disarming / Deceptive (eg. asking for the time or directions, etc.) When using this ploy your attacker is not only trying to lull you into a false sense of security, but also attempting to draw your attention away from his “line up” (ie: his intentions, and the position/posture from which he intends to launch his attack). If successfully executed, where you are taken by surprise, the effects can be devastating. Not only will you be unprepared physically for the attack and most likely receive the full brunt of the blow, but, more importantly you will be unprepared emotionally. Here, fear is your enemy, and to now be able to bring the resultant rush of adrenaline under control will be extremely difficult. There are, however, methods of training that can bring about the spontaneous control of adrenaline and, consequently, you will be more able to fight from this disadvantageous position.